This was a spontaneous pick for me; I had some time to kill in London while I was waiting for a flight to Venice, so I picked up a copy of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood from WHSmith. Usually airports are where I pick up more popular recent books, or terrible paperback crime thrillers, but they had an offer on the Penguin Modern Classics series- which I am collecting- so I went for that instead. My prior knowledge of the book was solely that I knew it was by the guy who wrote Breakfast at Tiffany’s. I seriously wasn’t expecting to be as impressed by it as I was.

So, it deals with the murders of four members of the Clutter family, by Perry Smith and Dick Hickock. Capote was granted a lot of access to the case as it was being investigated, and after the two killers were apprehended; his claim is that everything in the book is entirely factual, but some of the people who were there have disputed this. The main area which is disputed is the efficiency of the police; the lead investigator, Alvin Dewey, granted Capote special insight into the case, and a fairly common viewpoint seems to be that is resulted in a more favourable depiction than he may have deserved.

I fall on the side that, by and large, the book is pretty accurate, with a little artistic license here and there. I can safely say I’ve never read anything like it; somehow, it manages to alternate somewhere between a police report and an eloquent piece of literature, seamlessly. I’m really not sure how it works, but it does. What I thought did add to the plot was that there was no description of the murders or the motive until later in the book- even though the reader had been granted access into the upbringings and personalities of the killers from early on. I thought it was really effective, because it meant that as a reader- even though you know who’s committed the crime- you also move with the investigation in terms of finding out the how and why.

Despite really getting to know the killers, I didn’t find myself being able to sympathise with them. There was kind of two reasons for that I think. Firstly, the book really focuses on the Clutter family. We learn about how respected they are in their local community, the family dynamics and their personalities- you really get a sense of what a kind, god-fearing and genuine family they are. Second, because Capote never quite lets you get lost enough in his prose to forget that these two people are real killers. With fiction, I don’t struggle to sympathise with the murderers, Patrick Bateman, Hannibal Lecter and Dexter are some of the most interesting characters who I think have been put to paper- but they aren’t real.

Perry Smith, admittedly, is much more likable. Although, I got the impression he was given more “air time” than Dick; it is well known that Perry became very close to Capote, some say more than a little too close. Nonetheless, as a product of its time, presenting a murderer as fundamentally human and not solely a monster, is incredibly forward thinking. It is now commonplace that the “bad guy” has had some terrible upbringing or a complex personality which has impacted them later in life, but this was a brave depiction for a book released in the 1960’s.

The book is horrifying, largely due to the aforementioned bunch of sweet hearts that make up the Clutter family. They’re a very good fit for the ideal American Dream family, but it doesn’t come across as another hackneyed account, because they’re so genuinely nice. It becomes even more horrifying, when the murders are revealed to be so utterly senseless. It had been intended as a robbery, which would leave no witnesses. Perry and Dick left with around $50 dollars, a radio and a pair of binoculars- what they had expected to find was a safe containing around $10,000, but this safe did not exist. Dewey compares the murders to the whole family being struck by lightning, for the sheer random senselessness of the event- and that is probably the most accurate comparison I have ever read.

I believe the most thought provoking passage of the entire book comes from Perry;

‘Am I sorry? If that’s what you mean- I’m not. I don’t feel anything about it. I wish I did…Why? Soldiers don’t lose much sleep. They murder and get medals for doing it. The good people of Kansas want to murder me- and some hangman will be glad to get the work. It’s easy to kill, a lot easier than passing a bad cheque.’

The questions raised about human nature here are fascinating- Perry is not devoid of emotion, but he feels that killing is easy. He is not a ‘typical’ murder who is desensitized to the world around him, and he is shown to have morals, just like anybody else. Perry still isn’t a character who I found likable, but he is disconcertingly human.

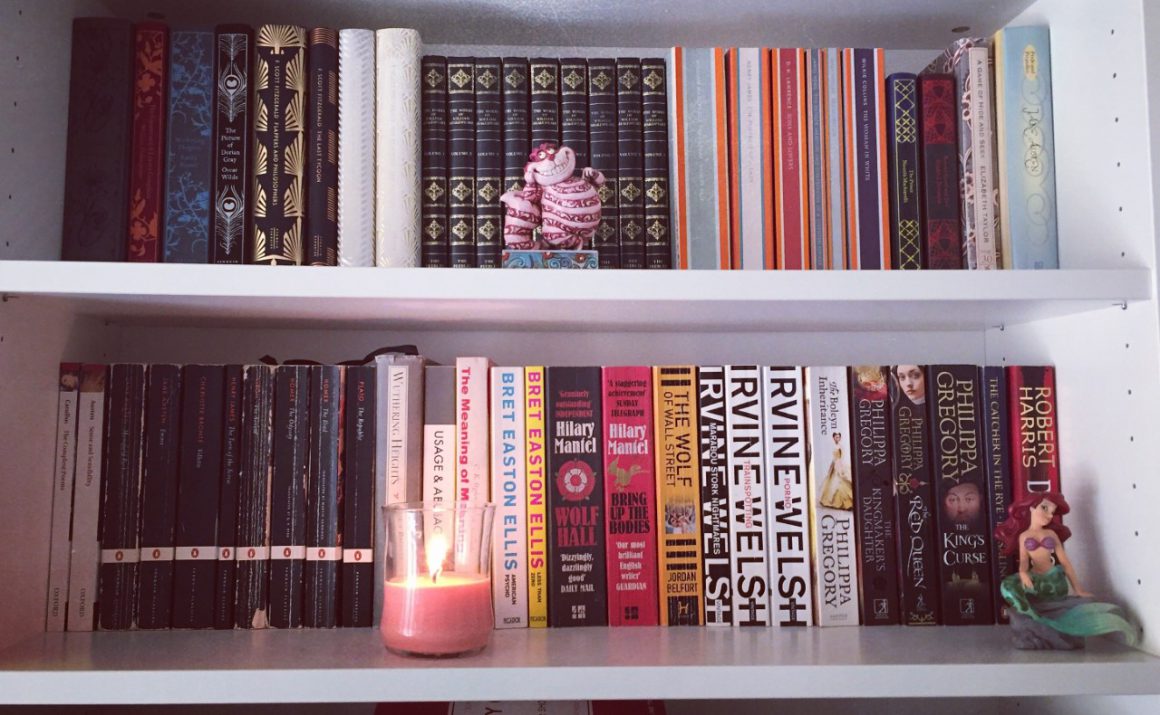

For anyone who might be reading ‘Portrait’ for the first time, I can’t recommend the Oxford World Classics edition enough. It has a brief but useful introduction, and plenty of really interesting further reading suggestions. There is also a godsend of a section which provides notes to some of the more confusing passages and provides context for some of the colloquialisms and contemporary allusions (so useful when dealing with Joyce).

For anyone who might be reading ‘Portrait’ for the first time, I can’t recommend the Oxford World Classics edition enough. It has a brief but useful introduction, and plenty of really interesting further reading suggestions. There is also a godsend of a section which provides notes to some of the more confusing passages and provides context for some of the colloquialisms and contemporary allusions (so useful when dealing with Joyce).